The Boar

The grunting got louder.

Now, I want to make something clear. I am not a coward. I have faced down Professor Grumthar during an unannounced quiz on mineralogy. I have eaten cafeteria fungus stew on a dare. I have looked Grandmaster Obrak Ironjaw in the eye while his portrait dripped with ceremonial ale. These are not the achievements of a coward.

But when the undergrowth at the bottom of the hill exploded and something the size of a small boulder came charging up the slope directly at me, I did briefly consider the merits of cowardice.

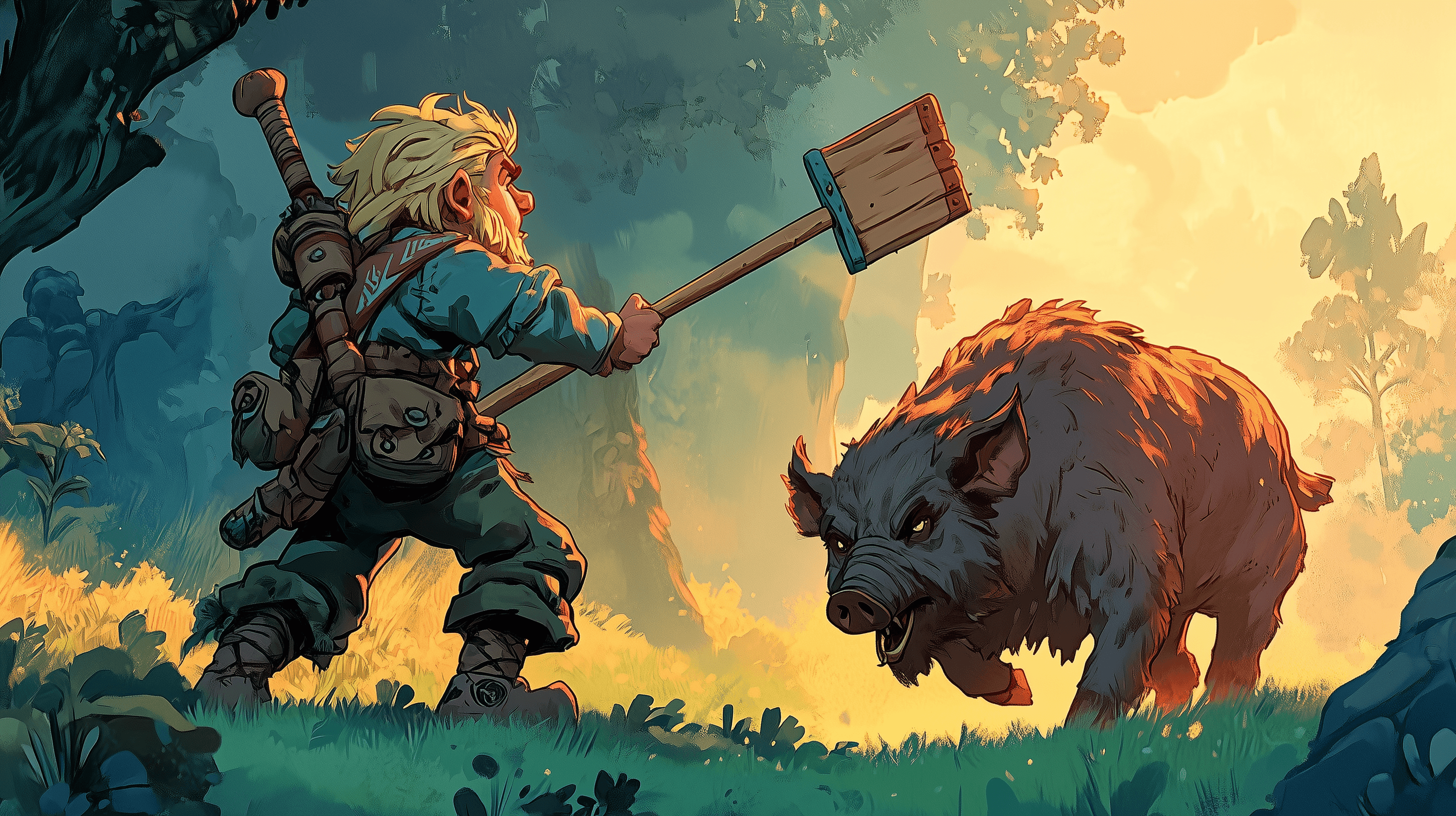

The boar was enormous. Not "large pig" enormous — "why does that pig have tusks the length of my forearm" enormous. It was black-bristled, mud-caked, and furious in the way that only a wild animal interrupted during dinner can be furious. Its eyes were small and red and deeply, personally offended by my existence. Its tusks curved upward like a pair of badly forged swords. It lowered its head, and it charged.

Straight at me.

I had approximately two seconds and the following inventory: one mop, one pair of soot-stained boots, and a book on portal theory that I appeared to have dropped during my involuntary transition between worlds.

The mop would have to do.

I planted my feet — which, let me tell you, is significantly harder on a grassy slope than on the stone floors of the Rumbling Deeps — and gripped the mop like a spear. The boar thundered closer. The ground vibrated. I could smell it now: mud and musk and the hot, damp breath of something that considered me a mild inconvenience between it and whatever it had been eating.

Here is what the physics book would have said, if it had a chapter on boar combat (it didn't; I checked): an object in motion tends to stay in motion. The larger the object, the harder it is to redirect.

The boar was very large. And very much in motion.

So instead of meeting it head-on — which would have been the brave thing to do, and also the dead thing to do — I did what any well-read, physically unimpressive dwarf would do.

I stepped sideways.

At the last possible moment, I threw myself to the right and swung the mop handle across the boar's path, low and hard, right at its front legs. It wasn't elegant. It wasn't heroic. It was, if I'm being honest, barely intentional.

But it worked.

The mop handle caught the boar across both front legs mid-stride. The boar, which had been expecting to connect with a dwarf-sized obstacle and was not prepared for the obstacle to suddenly not be there, stumbled. Its own momentum did the rest. Three hundred pounds of angry pork pitched forward, tusks plowing into the hillside, and somersaulted — actually somersaulted — past me in a spray of grass and mud.

It landed in a heap about ten feet uphill, legs flailing, making a noise that I can only describe as indignant.

I stood there, panting, holding the remains of my mop. The handle had snapped cleanly in half. The cave moss head had disintegrated entirely. I was holding a stick. A very short stick.

The boar scrambled to its feet. It shook its head. It turned to face me again. But something had changed. It looked at me differently now — not with less anger, exactly, but with a new quality. Confusion, maybe. Wariness. The look of an animal that had expected an easy target and received a mop to the shins instead.

We stared at each other. The boar snorted. I gripped my stick.

Then, very slowly, the boar turned, trotted to the edge of the clearing, and disappeared into the undergrowth. Not fleeing — nothing that big flees from anything. Just... deciding I wasn't worth the trouble. Which, honestly, was the most relatable decision anyone had ever made about me.

I waited until the crashing sounds faded. Then I sat down on the grass because my legs had decided, independently of my brain, that standing was no longer something they were willing to do.

I sat there for a while. The sun moved lower. The sky turned colors I'd only seen in the better paintings in the Grand Hall — orange and pink and a deep, impossible purple that made my chest tight for reasons I couldn't explain. The air smelled like a hundred things I couldn't name. A bird landed on a rock nearby, looked at me with immense disinterest, and flew away.

"Right," I said. To no one. "Right."